Religious Education (RE) is a subject that is compulsory in UK schools and colleges, for students aged 5 to 18. It has many aspects that echo with the vision of the BEADS foundation, in particular how it ‘appreciates and connects people from all religions, backgrounds and cultures, sacred and secular.’

RE (religious education) in the UK is considered a beacon for its inclusive, multi-faith approach which attempts to help young people understand the complex world of religion, morality and self-identity. It enables them to appreciate and respond to worldviews different from their own, and to understand how they are woven into the cultural and political make-up of society. In short, it tries to help future generations become more responsible and responsive members of our global community.

In 1995 I spent a year training to become a teacher of RE at St Martin’s College in Lancaster, a city in the north of England. The decision to study there was based on its being affiliated to the University where I had studied Eastern religions and Western philosophy ten years previously. What I didn’t know when I started the course, was that it was also at the cutting edge of a new approach to the subject known as Experiential RE, one promoted by my tutor, John Hammond.

RE in the UK had been gradually developing since the 1960’s when it had become part of the statutory national curriculum in state schools. It intended to try and help students understand and appreciate the increasingly multicultural make-up of society in this country, while at the same time hoping to help towards combatting increasing racism and prejudice. It had progressed from the 1940’s and 50’s, when only Christianity had been taught, to include the study of five other world religions: Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism. This choice reflected the faiths of many citizens in the UK, including those who had been invited to emigrate from Commonwealth countries after World War II.

RE in the UK had been gradually developing since the 1960’s when it had become part of the statutory national curriculum in state schools. It intended to try and help students understand and appreciate the increasingly multicultural make-up of society in this country, while at the same time hoping to help towards combatting increasing racism and prejudice. It had progressed from the 1940’s and 50’s, when only Christianity had been taught, to include the study of five other world religions: Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism. This choice reflected the faiths of many citizens in the UK, including those who had been invited to emigrate from Commonwealth countries after World War II.

However, by the 1970’s and 80’s there was a growing concern that RE in the UK had become merely a Thomas Cook’s Tour of world religions. That is, one where each religion was objectively and separately studied in relation to their outer form (their beliefs and practices, rituals, clothes, scriptures, buildings etc.), without referring to their inner, spiritual and ethical dimensions. There was also a need to build ‘bridges’ across the cultural gaps that were identified as separating the lives and subjective worlds of students, from those of the religious believers they were studying. Out of this need grew what became collectively known as Experiential Religious Education. Within this approach a whole array of creative and interactive means have been gradually developed to try to build and, to some extent, cross these ‘bridges.’

The main exponent of this drive was David Hay whose book, ‘New Methods in RE – An Experiential Approach’, became a key handbook for many teachers in the 1990’s and a key feature of my own teacher training course. As John Hammond writes:

‘Experiential RE addresses through the study of religion students’ hearts (and emotions, feelings and sense of identity) as well as their minds. The exercises are designed to engage emotions and concerns and provide a space where they can feel safe to reflect on who they are, their hopes and fears. The activities are always first person, about what ‘I’ really think and feel and so in this respect closer to the world of the adherent of spiritual practice or faith than that of the scientific scholar of religion.

Its aim was not to create religious experiences in classrooms but, by encouraging pupils to be sensitive to their own ‘inner experience’, help them understand the ways religious people experience the world. Because the exercises of Experiential RE could encourage an engaged, ‘first person’ involvement with human questions of identity, meaning and purpose, pupils learning in this way would be better able to appreciate the belief and practice of the world faiths.’

Many of the ‘exercises’ referred to above, involved the use of different practices such as: students visiting different places of worship; schools inviting people from the local community with a range of religious and humanist worldviews; the use of imagination and the imaginative use of art and creativity (involving symbols, narrative, drama, music, image, sound etc), meditation, stilling exercises, silence and guided fantasy; the experience of sharing in pairs, group work and circle time.

John Hammond again:

‘…. the exercises of Experiential RE provided a method for students to explore reflectively their own beliefs and engage in an informed and serious way with the commitments of others…. Like ritual, the learning processes of Experiential RE have religious or spiritual content, but like theatre the focus is not on commitment but learning…. The ability of experiential processes to motivate students and facilitate access to spiritual and religious realities means they are essential to successful RE…However, the ability to think through the processes, integrate them into a syllabus and manage them successfully in the classroom requires specific knowledge and skills on the part of the teacher.’

Over the years two main strands seem to have been identified as the basis for successful RE: ‘learning about’ religion (which drew upon the old ‘Cook’s tour’ approach); and ‘learning from’ religion (which had its feet in the new themes and interactive activities associated with Experiential RE).

In more recent times, however, the pressures on schools and teachers in the education system – relating to exam results and school ‘league tables’ – have impinged negatively on RE. Subsequently, it has become increasingly harder for RE teachers to justify the use of the more creative approaches relating to ‘learning from’ religion. This is because academic qualifications require a drier, more knowledge-based delivery – one largely involving the ‘learning about’ study of a much narrower range of religions.

Saying that, one saving grace is that this more academic drive still has the capacity to enable students to develop such core skills as critical thinking, empathy and listening skills, while also providing a space in the curriculum for self-reflection. It also creates an arena where controversial subjects can be safely discussed, especially those that might arise in exam topics focusing on moral issues such as: euthanasia, Just War theory, animal rights, abortion and the environment.

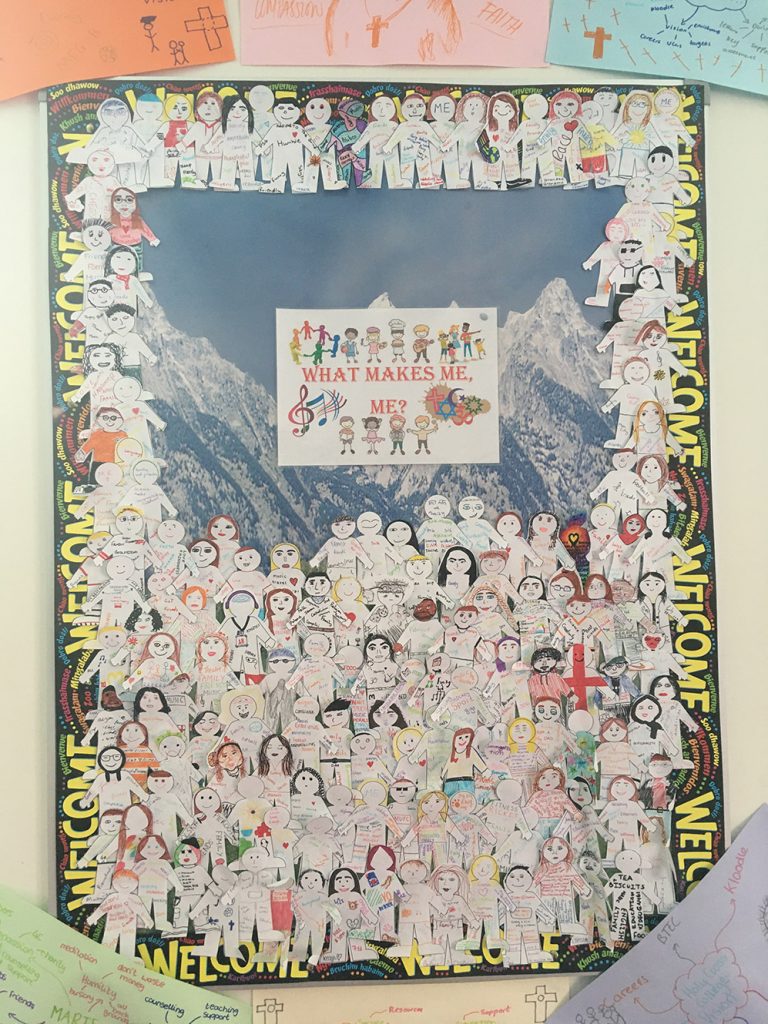

Over the years that I’ve been teaching, two words seem to best sum up what I feel good RE needs to be successful: relevant and engaging. Relevant to the daily lives of students and the kind of issues and dilemmas they might face in their futures. Engaging to their varied ‘learning styles,’ to their creativity and individual minds, hearts and senses. At times, this calls for an approach outside of the box, one which tries to incorporate the experiential ‘exercises’ mentioned above.

One teaching resource that I’ve developed, in an attempt at this approach, is called The Four Dimensions of Religion. It takes the form of a long-term project for students, one which has a wide range of activities meant to creatively engage their different learning styles in experiential ways. It’s also a way of dividing religions into more easily digestible parts, so as to enable students of all abilities to better understand them. The four parts I have focused on are entitled: Belief; Message; Moral and Social; Experience. Each part is subdivided into several others and are influenced by the ‘seven dimensions of a religion’ that the educator and lecturer Ninian Smart identified in his seminal book ‘The Religious Experience of Mankind’, and which had been essential reading for my degree course at Lancaster University.

During the project, we initially study a religion through the lens of these four dimensions (I chose Hinduism for this), before the students create their own imaginary religion project about any theme that interests them, one that uses as a framework the four dimensions. Within the parameters of reason and political correctness, this theme can be about anything: from a hobby to a favourite celebrity, from a value they cherish to a computer game or imaginary world of their own making…the world is their oyster. It has proved successful, for not only does it engage students of all abilities in creative ways, but also relates to something in their individual lives that is important, maybe even sacred, to them. In short, I believe it promotes empathy and acceptance within students and is a way of building bridges between their own lives and backgrounds, with those of religious believers. So that, in the words of the Beads vision statement, it helps them experience how good RE ‘appreciates and connects people from all religions, backgrounds and cultures, sacred and secular.’

Wayne Smith